In the previous post we have computed the Padé approximants for the function. The approximation was not very impressive compared to the Maclaurin series of

since the latter converges for all

. In this post we will have a look at the Padé approximants and Maclaurin series of

.

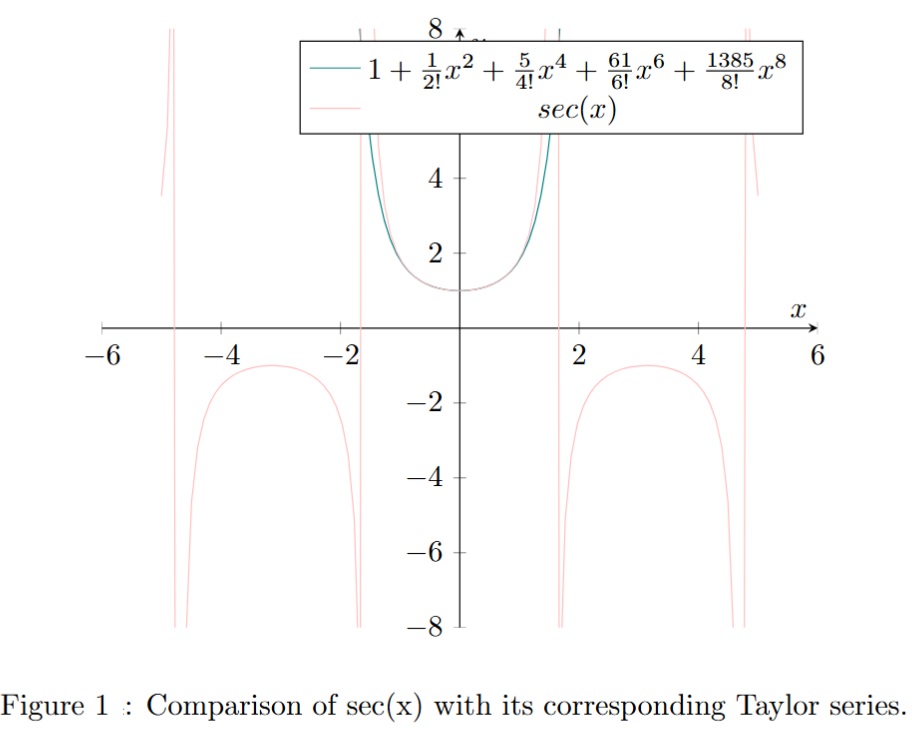

First let’s recall the graph of (see figure 1).

is a function with vertical asymptotes that cannot be approximated globally by a Taylor series. The Maclaurin series of

is:

Where are so-called Euler numbers:

We would like to compute the approximant of

. The first step is to have a look at the corresponding Hankel determinant (which is the determinant of the Hankel matrix):

For and

we have:

and the corresponding Hankel determinant for the of

is:

the determinant being not equal to zero implies that we can inverse the Hankel matrix and solve the systems to compute the Padé coefficients of for

(see post Computing Padé approximants). The inverse of the Hankel matrix is given by:

We have to solve this first linear system:

Solving the system above allows us to compute the coefficients (see results below). Now, according to the calculations presented in the post (see Computing Padé approximants), we have to solve the second linear system to compute the

coefficients:

This implies that for :

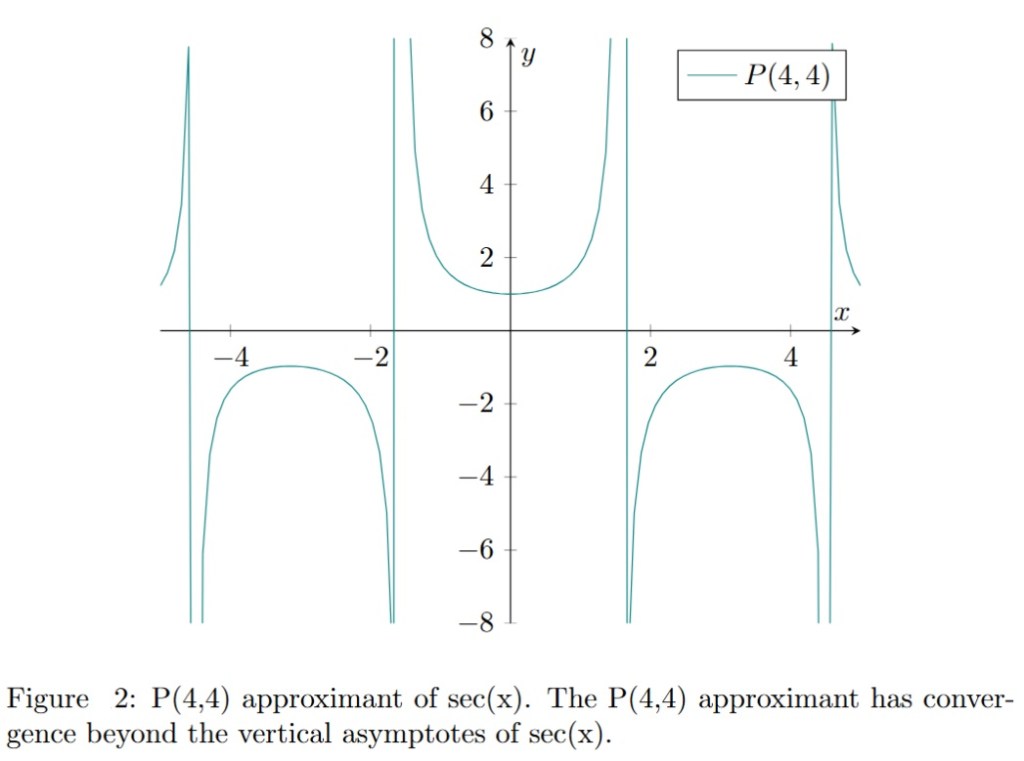

The graph of for

is presented in figure 2. The graph of

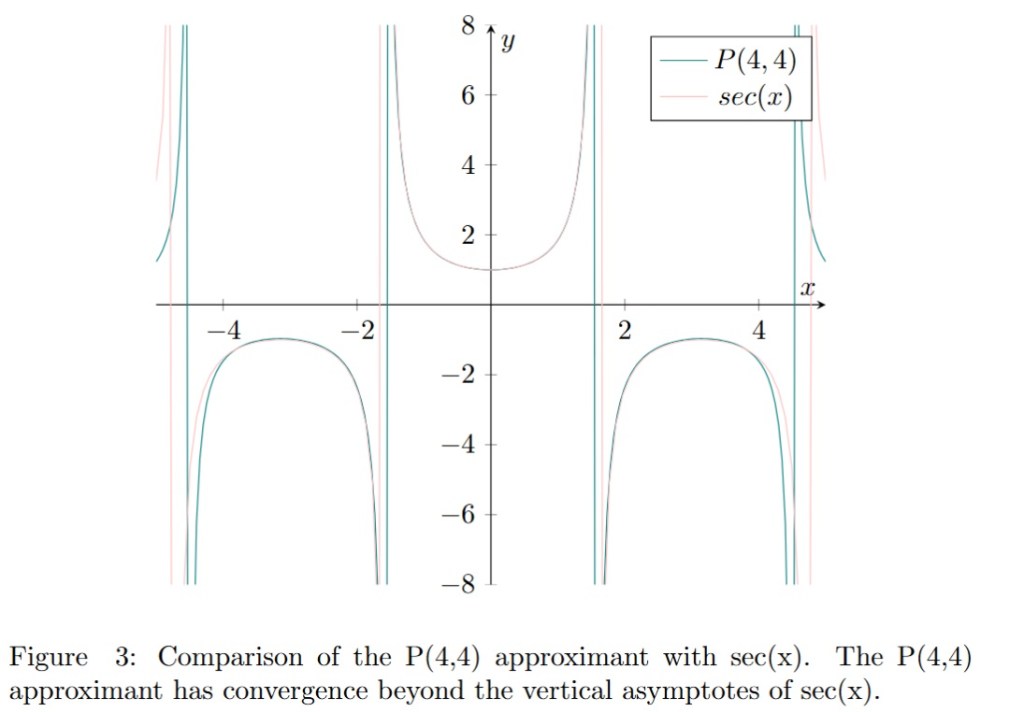

and its corresponding

is presented in figure 3. We can see that the

approximant (in green) is approximating the function

beyond its vertical asymptotes (pink vertical lines) in contrast to the corresponding Taylor series presented in figure 1. Moreover the convergence of

is better than the one of the Taylor series.

It is also interesting to note that the ‘information’ needed to construct the Padé approximants of the function has been extracted from the truncated Taylor series. Despite this fact, the Padé approximant provides a better approximation of the

function than the series from which it is derived.

Leave a comment