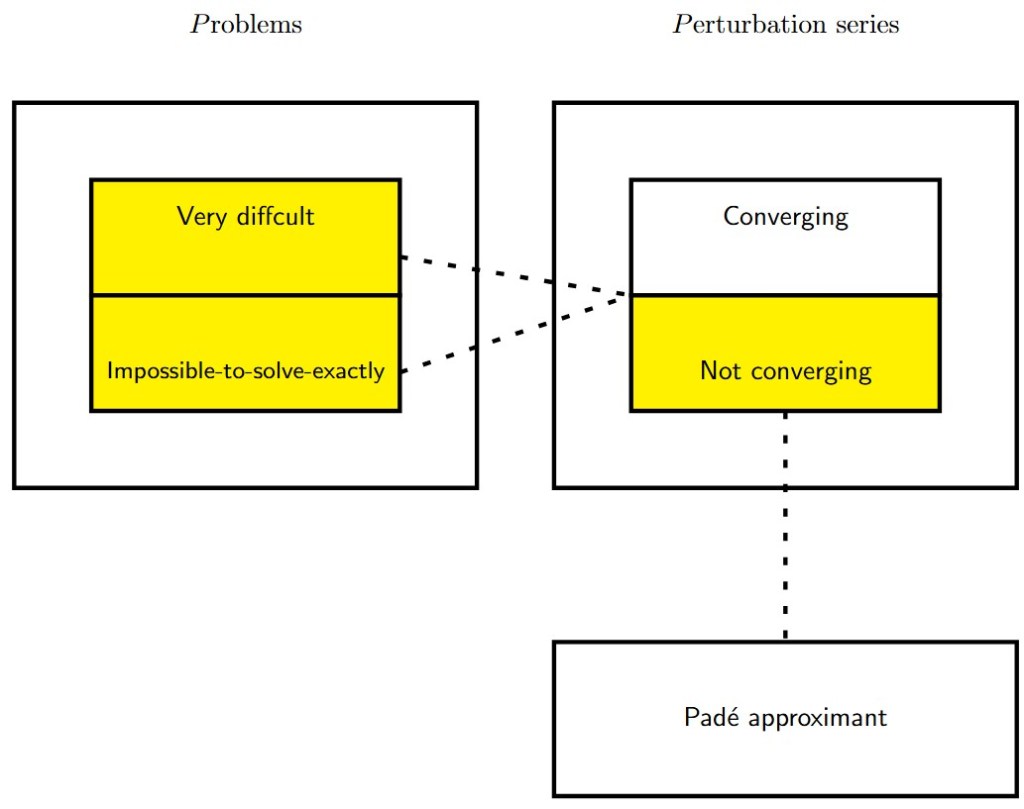

For a function analytic at

, with Taylor series

valid within its radius of convergence , the Padé approximant of order

, denoted

with

and

, satisfies

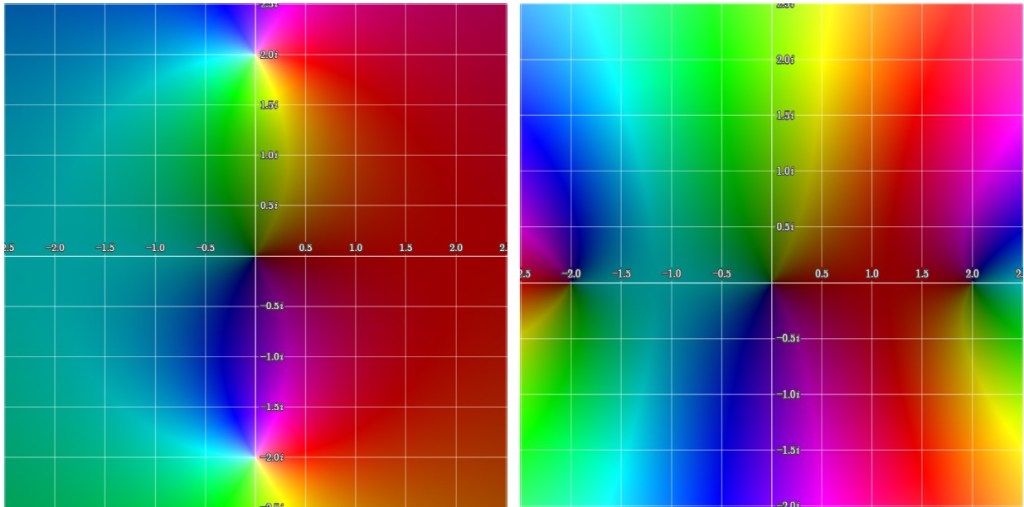

near . The rational structure of

allows it to approximate

beyond the disk

by modeling singularities (e.g., poles or branch points) through the zeros of

. This enables analytic continuation into regions where the Taylor series diverges.

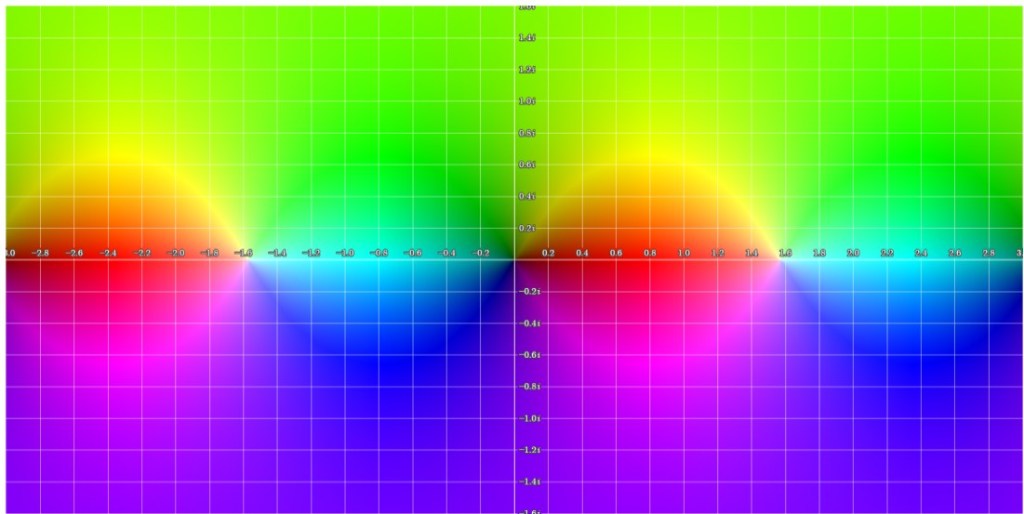

Formally, for a meromorphic function in a domain

, the diagonal Padé approximants

often converge to

in

, where

is the set of poles of

:

Let be meromorphic in a domain

, with a set of poles

of finite total multiplicity. The diagonal Padé approximants

, defined as rational functions

satisfying

near , converge uniformly to

on compact subsets of

as

.

The zeros of approximate the poles in

, enabling analytic continuation of

beyond the radius of convergence of its Taylor series.