The basic idea beyond Padé approximants is to construct a rational fraction whose Taylor series expansion near the origin coincides with that of a given function up to the maximum order. In the previous sections we introduced Padé approximants and a procedure to calculate their coefficients by solving 2 systems of linear equations sequentially (see this post).

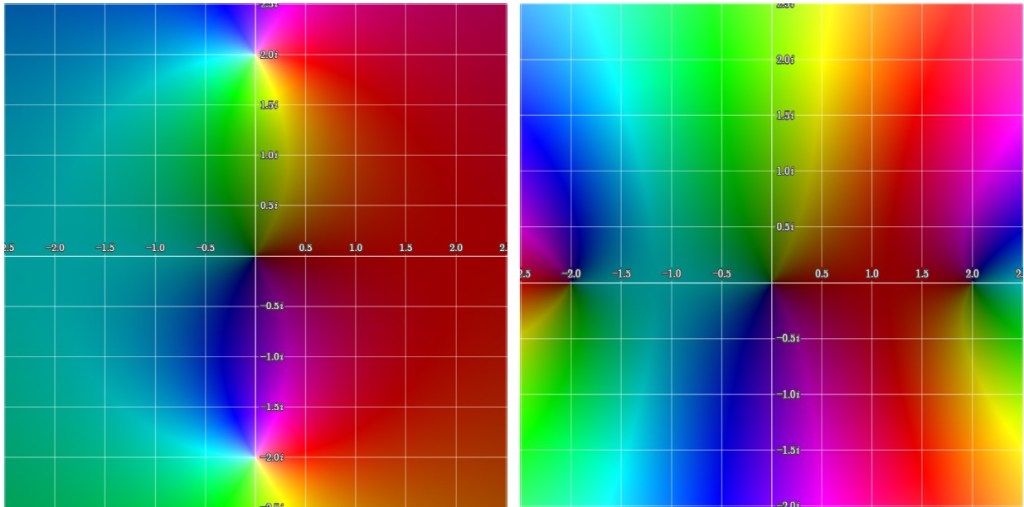

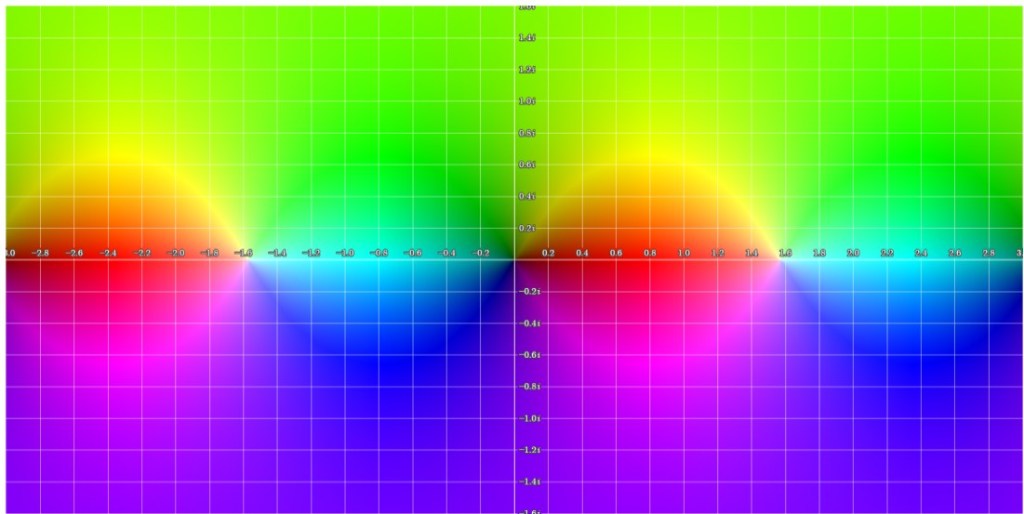

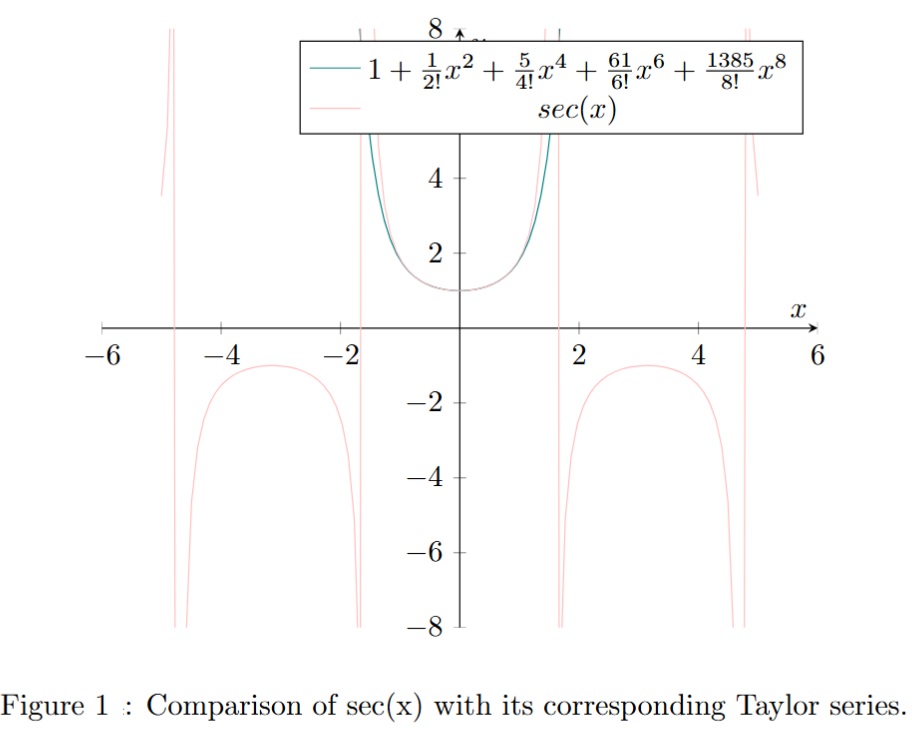

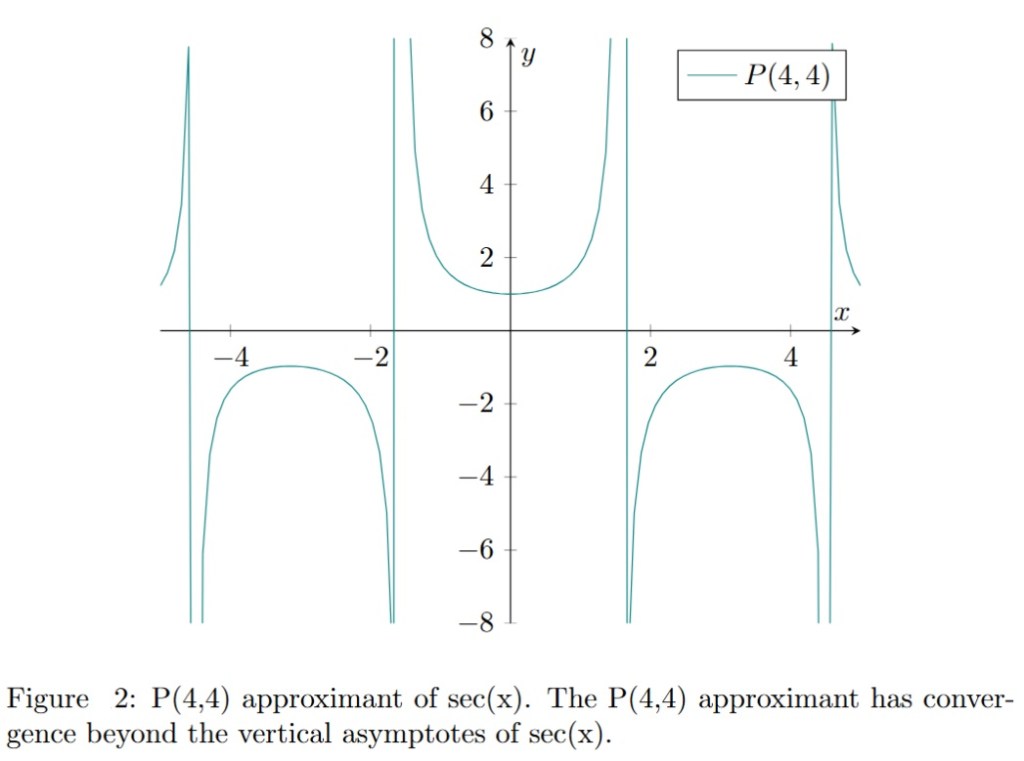

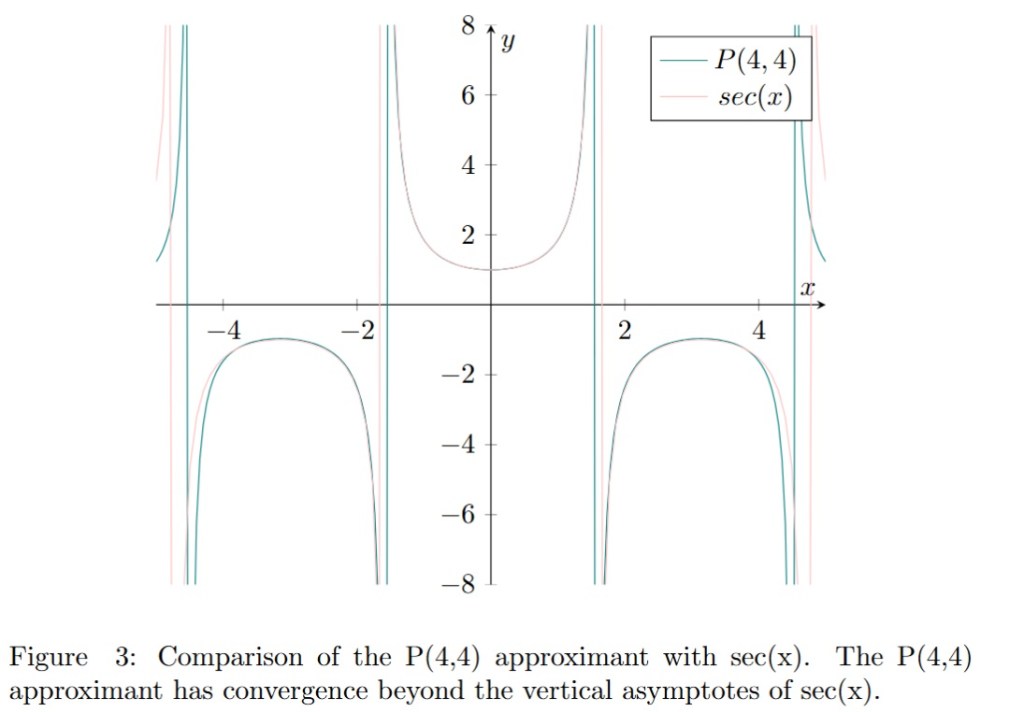

We have observed (in particular through the examples concerning and

) that Padé approximants:

Converge beyond the disc of convergence of the entire series

Speed up convergence

Extend the notion of series

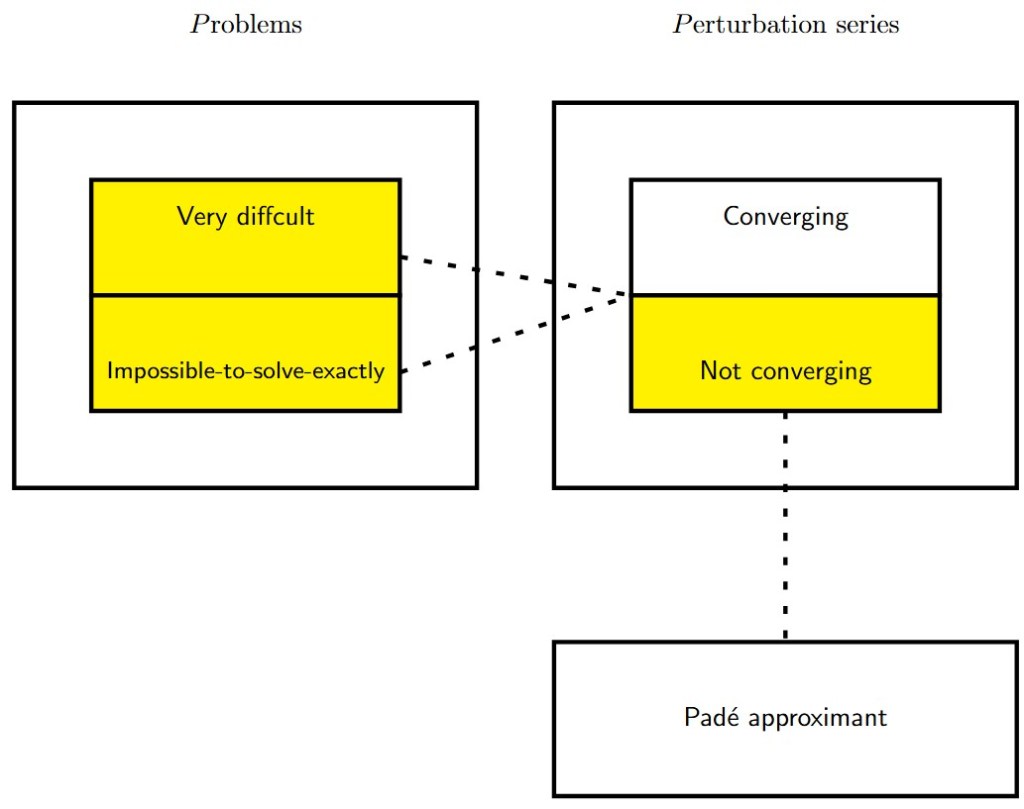

Now, let’s imagine that we want to solve a problem that is very difficult or even impossible to solve exactly (i.e. a specific differential equation, extracting the roots of a polynomial, etc.). We can split the problem into an infinite number of simple problems. This is the principle of perturbation theory (which is in many cases the only way to solve the problem). The result of such a procedure is a geometric series (we will see this later). In a very large number of cases, this series does not converge. In these cases, we can use Padé approximants to ‘extract’ the information contained in the series and finally obtain a convergent rational function (as illustrated in the case of the functions and

).

The figure below presents schematically a potential application of Padé approximants in this context.