Consider the archetypal divergent series

In a previous post we have seen the Borel summation of

Step 1 – Ordinary Borel summation

The ordinary Borel summation fails for  the analytic continuation of

the analytic continuation of  has a simple pole at

has a simple pole at  lying on the positive real axis. The ordinary Borel integral

lying on the positive real axis. The ordinary Borel integral

therefore diverges for all  (the pole blocks the integration path).

(the pole blocks the integration path).

Step 2 – Borel–Écalle summation

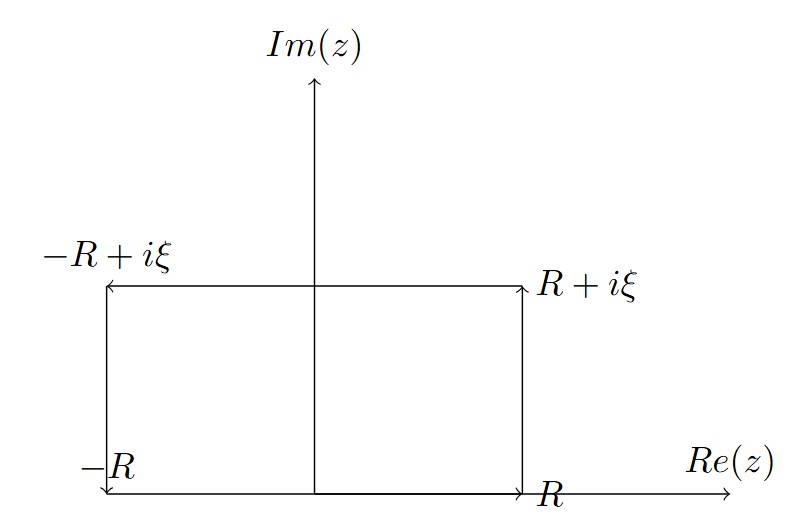

Define the two lateral Borel transforms by deforming the contour slightly above (+) or below (-) the real axis:

The notation ∞e±i0 means that the upper limit of integration is taken to infinity along a ray that approaches the positive real axis from above (angle +0) or from below (angle −0). This slight contour deformation is necessary when the integrand has a singularity (here at t = 1/x) on the positive real axis itself, which would cause the ordinary Borel integral to be ill-defined.

These integrals exist, and

The Borel–Écalle summation is defined by

And in this case:

where  is the exponential integral function. Thus, despite the divergence of the original series and the failure of ordinary Borel summation due to the pole on the integration path, the Borel–Écalle median summation recovers the exact analytic continuation on the positive real axis.

is the exponential integral function. Thus, despite the divergence of the original series and the failure of ordinary Borel summation due to the pole on the integration path, the Borel–Écalle median summation recovers the exact analytic continuation on the positive real axis.

and

and therefore:

and

:

and

:

are Bernoulli numbers.