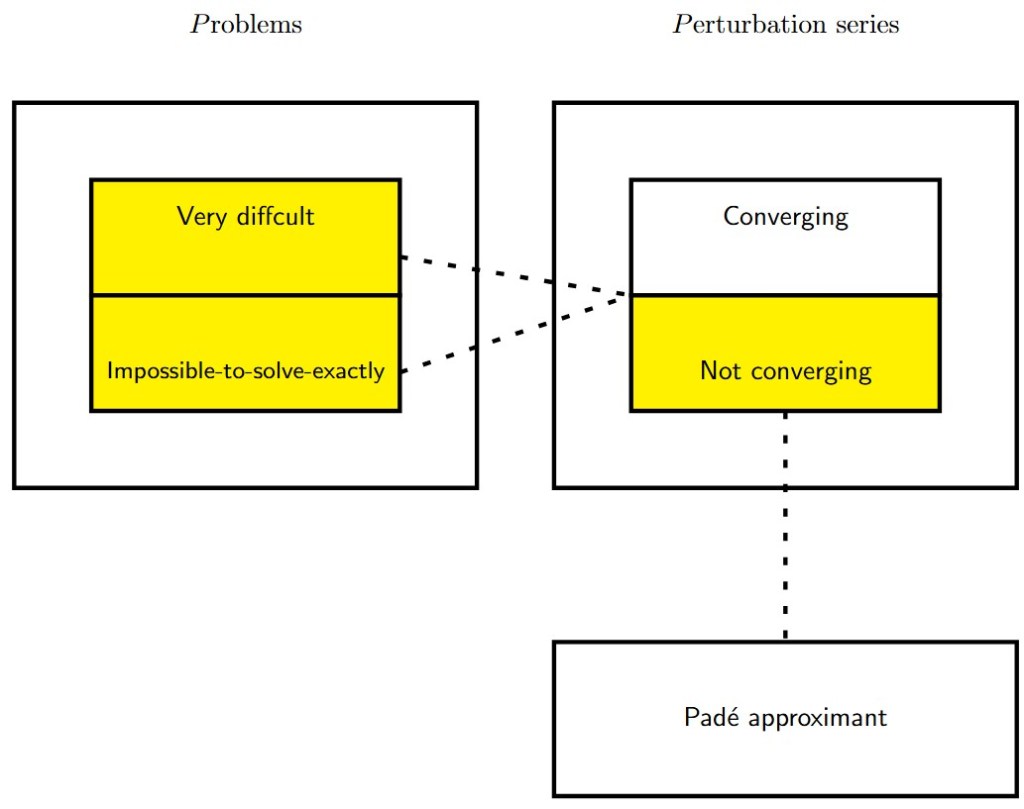

In this post, we provide readers with Python code that enables the derivation of Padé approximants from series coefficients given as input to the algorithm in the form of a coefficient vector. It is also necessary to predefine the degree of the numerator and denominator.

import sympy as sp

def pade_approximation_function(series, m, n):

"""

Returns the Padé approximation [m/n] in the form of a rational function

with coefficients simplified as fractions.

Parameters:

series : list - Coefficients of the Taylor series (e.g., [1, 0, -1/2, 0, 1/24, ...] for cos(x))

m : int - Degree of the numerator

n : int - Degree of the denominator

Returns:

sympy.Expr - Rational function P(x)/Q(x) with simplified fractions

"""

# Check that there are enough terms in the series

if len(series) < m + n + 1:

raise ValueError(f"The series must contain at least {m + n + 1} terms for an [m/n] approximation")

# Convert the series coefficients to simplified fractions

series = [sp.simplify(sp.Rational(str(c))) for c in series]

# Symbolic variable

x = sp.Symbol('x')

# Coefficients of the numerator P(x) = a0 + a1*x + ... + am*x^m

a = [sp.Symbol(f'a{i}') for i in range(m + 1)]

# Coefficients of the denominator Q(x) = 1 + b1*x + ... + bn*x^n (b0 = 1)

b = [1] + [sp.Symbol(f'b{i}') for i in range(1, n + 1)]

# Polynomials P(x) and Q(x)

P = sum(ai * x**i for i, ai in enumerate(a))

Q = sum(bi * x**i for i, bi in enumerate(b))

# The truncated series in polynomial form

S = sum(c * x**i for i, c in enumerate(series))

# Equation to solve: P(x) - Q(x)*S(x) = 0 up to order m+n

expr = P - Q * S

# Extract coefficients of x^0 to x^(m+n) and set the equations to 0

equations = [sp.expand(expr).coeff(x, k) for k in range(m + n + 1)]

# Variables to solve for (a0, a1, ..., am, b1, b2, ..., bn)

unknowns = a + b[1:]

# Solve the system

solution = sp.solve(equations, unknowns)

if not solution:

raise ValueError("No solution found for this approximation")

# Simplified coefficients for P(x) and Q(x)

num_coeffs = [sp.simplify(sp.Rational(str(solution[ai]))) if ai in solution else 0 for ai in a]

den_coeffs = [1] + [sp.simplify(sp.Rational(str(solution[bi]))) if bi in solution else 0 for bi in b[1:]]

# Construct the final polynomials

P_final = sum(coef * x**i for i, coef in enumerate(num_coeffs))

Q_final = sum(coef * x**i for i, coef in enumerate(den_coeffs))

# Return the simplified rational function

return sp.simplify(P_final / Q_final)

Here is the code to compute the Padé(2,2) for

# Compute Padé(2,2) for cos(x)

series = [1, 0, -sp.Rational(1,2), 0, sp.Rational(1,24)]

m, n = 2, 2

pade_approx = pade_approximation_function(series, m, n)

print("Padé(2,2) approximant for cos(x):")

sp.pprint(pade_approx)