In the previous posts, we have seen that in order to compute the Padé coefficients  corresponding to a given geometric series we have to be invert the following matrix:

corresponding to a given geometric series we have to be invert the following matrix:

Where  are the coefficients of the Taylor series. The matrix above is called a “Hankel matrix”. A ‘Hankel Matrix’ is a symmetric square matrix in which each ascending skew-diagonal from left to right is constant. For Example a Hankel matrix of size 5 can be written like this:

are the coefficients of the Taylor series. The matrix above is called a “Hankel matrix”. A ‘Hankel Matrix’ is a symmetric square matrix in which each ascending skew-diagonal from left to right is constant. For Example a Hankel matrix of size 5 can be written like this:

Let’s make some observations on the Hankel determinant  :

:

This determinant has n colons and n rows. We can also numerate the terms of the determinant following the notation:

Where  etc. This notation of the terms of the determinants implies that:

etc. This notation of the terms of the determinants implies that:

So that:

If  is a even function of class

is a even function of class  , we see that odd coefficients

, we see that odd coefficients  . In this case, every second term of in the Hankel matrix is zero. If

. In this case, every second term of in the Hankel matrix is zero. If  is even, we can establish that if

is even, we can establish that if  and

and  are odd then the Hankel determinant is zero:

are odd then the Hankel determinant is zero:

The term with index  of the Hankel determinant is

of the Hankel determinant is  . As stated before, this term is zero for an even function if

. As stated before, this term is zero for an even function if  is odd. Now, if

is odd. Now, if  and

and  are odd this means that

are odd this means that  is even and

is even and  is odd when

is odd when  is even. It follows that, in the case of an even function, the Hankel determinant is of the form:

is even. It follows that, in the case of an even function, the Hankel determinant is of the form:

We observe that the odd rows of this determinant are linear combinations of:

This implies that odd-numbered columns are linked and therefore the determinant is zero.

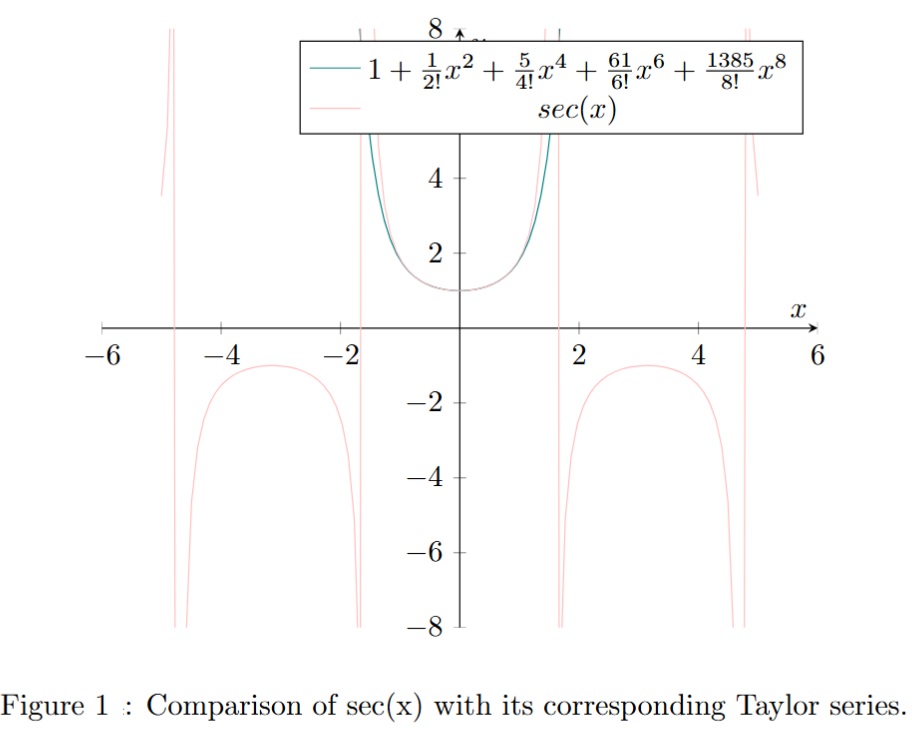

As example we will derive the  of the cosine function. First we have to consider the geometric series of degrees up to

of the cosine function. First we have to consider the geometric series of degrees up to  of cosine:

of cosine:

For  and

and  (

( and

and  are both odd) the Hankel determinant is:

are both odd) the Hankel determinant is:

The corresponding Hankel determinant for calculating the coefficients of the  Padé approximant of the geometric series of cosine is therefore:

Padé approximant of the geometric series of cosine is therefore:

This implies that we cannot calculate the  approximant for the cosine function.

approximant for the cosine function.

In conclusion, for an even function like cosine, when m and n are odd, the Hankel determinant Hn,m(f) is zero due to the linear dependence of the columns.

and

. The Maclaurin series of

is:

is:

we therefore have to first solve:

coefficients calculated above in the second linear system we have:

,

,

. Therefore:

we have to first solve:

coefficients calculated above in the second linear system we have:

,

,

. Therefore:

then:

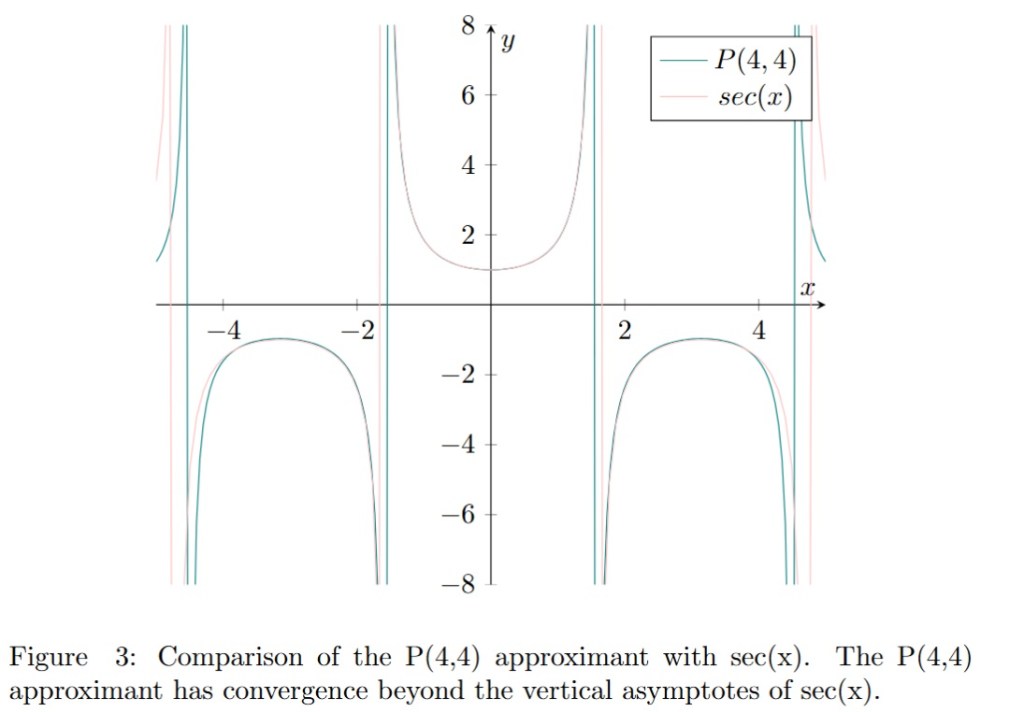

and

are the Padé approximants of

and

respectively. This proposition is actually true and can be proved formally.